A Complex Urban Fabric

The Rotonda baths form part of an urban context of great richness and complexity. Urban growth following the 1693 earthquake was regulated by the city Senate which decided to organize the areas available ( for reconstruction ) by dividing the city along a conventional line: to the east ( Piazza Duomo and Via Vittorio Emanuele) the value of the land was higher, while to the west ( beyond Via Plebiscito and in the area of the ancient acropolis) it was clearly lower. In the eastern, most prestigious part, the opening up of main roads ( today known as Via Etnea, Via Vittorio Emanuele, Via Garibaldi) meant that the areas already destined for use by the wealthy nobility and ecclesiastical orders were further enhanced. To the west instead there was a concentration of poorer residential building that developed around what was left of the medieval town, without taking into account the planning rules laid down by the Duke of Camastra. Within this tight knit of blocks, roads and alleys ( opposite the Rotonda is very atmospheric Vicolo Maura) are some of ancient Catania’s most significant monuments: the Roman Theatre and the Odeum, the baths in Piazza Dante ( in front of the monumental entrance to the Benedictine monastery complex), remains of the Norman fortifications ( in the grounds of the Liceo Spedialieri), a 1500s bastion known as the Bastione “degli Infetti”, of the infected, and two Aragonese reinforcement towers (the one known as “del Vescovo” , the Bishops’s, is visible at the height of Via Plebiscito). Within the intricate mixture of old and modern buildings, these remains of the past take shape as you penetrate into the maze of old buildings and workshop.

From Roman Baths to the Church

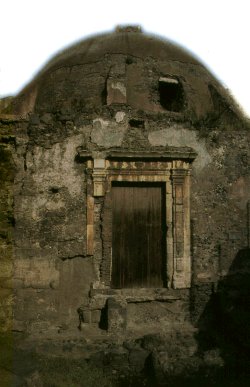

The thermae complex known as the “Rotonda” is situated to the north of the ancient theatre. The current entrance is on the road of the same name, Via della Rotonda, which goes up towards the summit of the hill which was Catania’s acropolis. This building survived the 1693 earthquake (as did many of Catania’s monuments) and has been studied by many experts who felt sure that building was the model for the Pantheon in Rome: because of this mistake in interpretation the building was commonly called the Pantheon and still today some guidebooks carry this atmospheric and imaginative name. In the 1700s the Prince of Biscari recognized the monument as a baths complex, but it was the excavation work conducted in 1950 by G. Libertini that provided the building with a more accurate historical location and chronology.

The excavation work allowed for identification of the exact plan of the building, its original height and the basic structure which appeared to have been changed by successive alterations.

It is circular in construction, enclosed within a quadrangle and with a series of marble arches and tanks arranged within large niches. Under a recent floor and a crypt that had been dug below it, the ancient constructions came to light, organized following a coherent chronological scheme that we reproduce here:

1) Hellenic- roman level with remains of the thermae constructions

2) An alteration dating to Roman imperial times which gave the room the circular calidarium shape.

3) Another alteration dating to a later Roman era.

4) The Byzantine floor.

5) Some medieval alteration.

6) The most recent alterations dating to the seventeenth or eighteenth centuries.

From this scheme it is possible to reconstruct the troubled history of this building that was transformed from Roman baths into a Christian church.

Two barely visible frescoes on the walls are linked to the Christian phase: one probably represent Saint Gregory the Thaumaturge and the other a Madonna with the Child Jesus.

copyright Giuseppe Maimone Publisher